[Johnathan Clayborn]

More and more I am beginning to realize that not everything that can be considered "truth" can be measured empirically. Often we write our own truths via our perceptions. Other times, we allow ourselves to be fooled by things that sound logical on the surface. A clever story can appear truthful on the surface, even if it is entirely inaccurate. I came across an example of this earlier this week that I will share here, during which time I will break it down and explain how this story, which appears to make logical sense, is largely inaccurate.

The story starts with a preface:

This is soooo interesting!! Totally feeling pretty blessed right now and not "piss poor"!

They used to use urine to tan animal skins, so families used to all pee in a pot & then once a day it was taken & Sold to the tannery.......if you had to do this to survive you were "Piss Poor"

But worse than that were the really poor folk who couldn't even afford to buy a pot......they "didn't have a pot to piss in" & were the lowest of the low. The next time you are washing your hands and complain because the water temperature isn't just how you like it, think about how things used to be.

In this first part the author of this tall tale begins with an element of truth; yes, tanners in the ancient world did use urine during the tanning process, particularly in Ancient Rome. This practice was well documented. However, this is not where the term "piss-poor" comes from. According to the Etymology Dictionary the term "piss" as an amplifier dates from WWII. And, in this particular case "poor" wasn't a reference to their financial status, but rather the quality of their work; ie: a Piss-poor mechanic. The first example of such is from 1940: Piss-rotten. The first recorded instance of Piss-poor comes from 1946. And while "didn’t have a pot to piss in" is an idiomatic expression which portrays destitution, it is also not from the 1500's. It first appeared in print in "Nightwood" by Djuna Barnes, which was published in 1936. The story goes on...

Here are some facts about the 1500s:

Most people got married in June because they took their yearly bath in May, and they still smelled pretty good by June.. However, since they were starting to smell . ...... . Brides carried a bouquet of flowers to hide the body odor. Hence the custom today of carrying a bouquet when getting Married.

Brides carrying flowers had nothing to do with their use as an air freshener. Flowers were symbols of fertility and feminism and it was believed that carrying flowers on their wedding day would bring a couple luck in conception. Also, bathing once per year was wrong. The lower class people did not bathe at all, for fear that the bath water would widen their pores and expose them to terrible diseases. The upper class people did tend to bathe, but they did so a handful of times each year, and certainly not on any set schedule.

Baths consisted of a big tub filled with hot water. The man of the house had the privilege of the nice clean water, then all the other sons and men, then the women and finally the children. Last of all the babies. By then the water was so dirty you could actually lose someone in it.. Hence the saying, "Don't throw the baby out with the Bath water!"

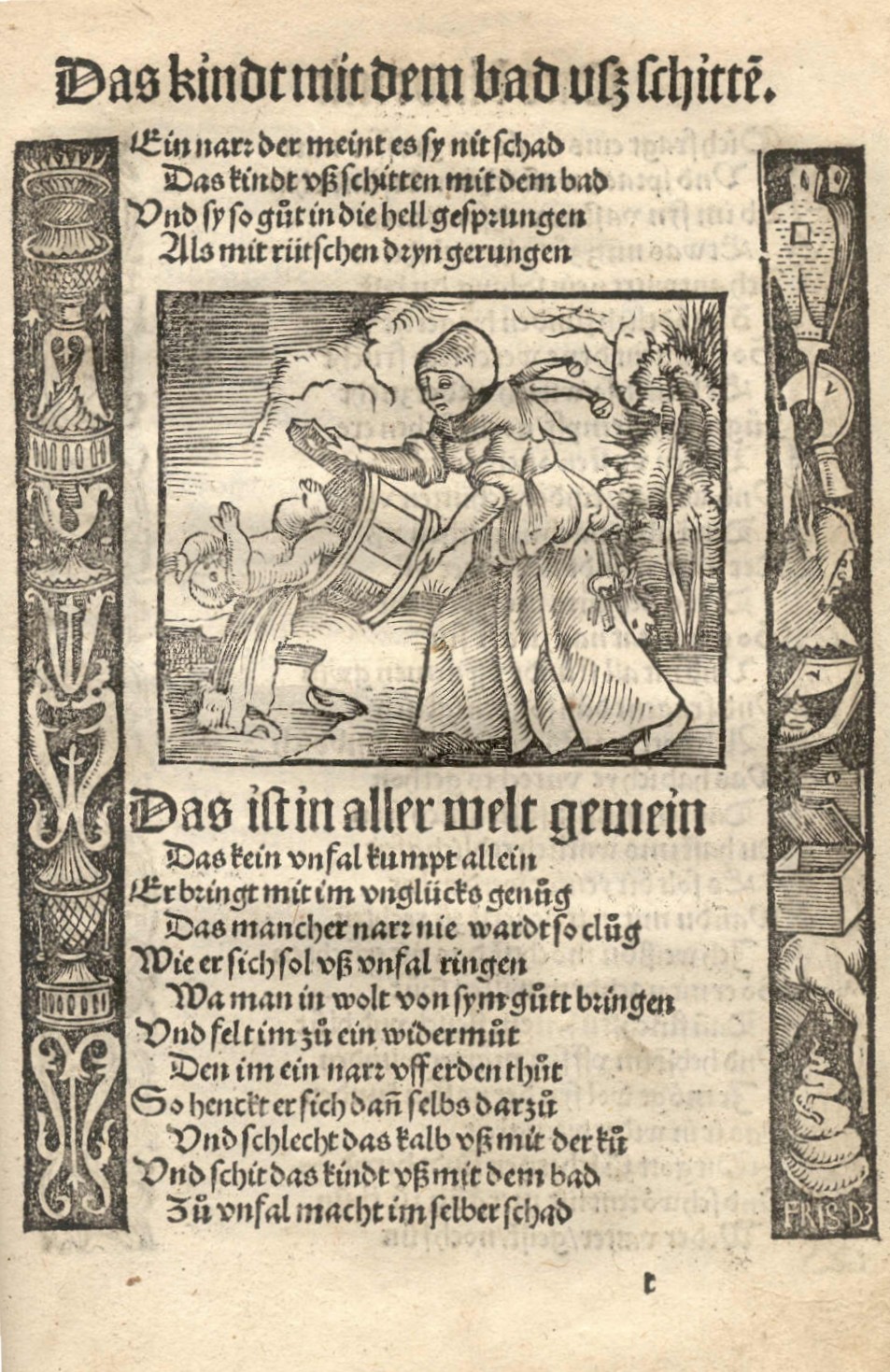

This is also incorrect. In many medieval cities there were public bath houses, which were common features since the Greco-Roman times. Aristocratic nobles who had a private bath often had a tub that was made from copper, bronze, or stone, so picking it up to dump it out would have been, for all intents and purposes, impossible. There was no modern plumbing during the 1500s, so filling up an entire tub with enough water to bathe an adult would have been a feat in and of itself, let alone the feat of engineering that would have been required to heat that amount of water. Poor people who did bathe and did not have access to a bath house typically just bathed in the local steam or pond. Now, to be fair, the phrase "don't throw the baby out with the bathwater" first appeared in 1512 in Germany. It was written by Thomas Murner in the book Narrenbeschwörung (Appeal to Fools). Scholars question the intent of this expression since the work in which it appears is satirical in nature. In the accompanying woodcut illustration the bucket that the woman is holding is clearly not large enough for an adult, which would lend support to the idea that the author was using this expression in an allegorical manner.

Houses had thatched roofs-thick straw-piled high, with no wood underneath. It was the only place for animals to get warm, so all the cats and other small animals (mice, bugs) lived in the roof. When it rained it became slippery and sometimes the animals would slip and fall off the roof... Hence the saying "It's raining cats and dogs."

Mice and bugs did, in fact, live in the straw thatched roof, that is certain. However, cats, and especially dogs, did not venture up there. The terms "raining cats and dogs" first appeared in the 17th century, not the 16th. There are number of theories about the meaning of this term, but the most widely accepted theory is that it is intended to evoke the image of a tumultuous engagement of a cat and dog fighting which the speaker is trying to equate the ferocity of the downpour to.

There was nothing to stop things from falling into the house. This posed a real problem in the bedroom where bugs and other droppings could mess up your nice clean bed. Hence, a bed with big posts and a sheet hung over the top afforded some protection. That's how canopy beds came into existence.

Canopy beds actually existed prior to the 1500s. The first iterations of these beds were used by nobles and aristocrats for two pragmatic purposes. The original canopy beds also featured curtains around all four sides that could be drawn closed. The first purpose that this served was to afford the sleeper some privacy from any other people who may also be sleeping in the room. But, more importantly, there was a mini-ice age going on during the middle ages and this curtain system provided extra warmth. Keeping the sheets clean would have been an added benefit and a by-product of the first two issues, but this is ignoring the fact that most nobles who could have afforded canopy beds would also likely have had solid roofs with wooden shingles.

The floor was dirt. Only the wealthy had something other than dirt. Hence the saying, "Dirt poor." The wealthy had slate floors that would get slippery in the winter when wet, so they spread thresh (straw) on floor to help keep their footing. As the winter wore on, they added more thresh until, when you opened the door, it would all start slipping outside. A piece of wood was placed in the entrance-way. Hence: a thresh hold.

"Dirt Poor" is not even a British expression, it's an American one, so there's no way that it dates from the 16th Century. Dirt Poor comes from the American Great Depression and is in reference to the Dust Bowl.

Also, people didn't add "thresh" to their floors. They kept Rush on the floor. Rush is a type of long, flowering grass. In modern times some places, particularly parish churches, will perform acts known as "rushbearing", where rushes are gathered up and strewn on the floor. While the lower classes would have probably used loose rushes, most higher status houses would have been furnished with woven mats made of rush. The term "thresh" means, "to trample". The threshold is the first place that you step inside of the home. Presumably you would trample the rush on the floor, but thresh is a verb, not a noun, so a threshold isn't used for keeping "thresh" inside.

In those old days, they cooked in the kitchen with a big kettle that always hung over the fire.. Every day they lit the fire and added things to the pot. They ate mostly vegetables and did not get much meat. They would eat the stew for dinner, leaving leftovers in the pot to get cold overnight and then start over the next day. Sometimes stew had food in it that had been there for quite a while. Hence the rhyme: Peas porridge hot, peas porridge cold, peas porridge in the pot nine days old.

Almost. Yes, most meals cooked in the pot were stew, and yes pease porridge could sit there for a couple of days, but often not more than 2 or 3 and only to improve the flavor. Peasants diets consisted of lots of breads and grains, including beer (beer was actually more sanitary than regular water). However, according to most accepted understanding of human development, such as that outlined by Professor Jared Diamond in Guns, Germs, and Steel, getting meat would not have been particularly difficult. Cows, Pigs, Chickens, and Sheep were among the first four animals domesticated for food. Even peasants would have had access to one of these on a pretty regular basis. Also, the leftover stew was often eaten for breakfast the next morning.

Sometimes they could obtain pork, which made them feel quite special. When visitors came over, they would hang up their bacon to show off. It was a sign of wealth that a man could, "bring home the bacon." They would cut off a little to share with guests and would all sit around and chew the fat.

As Dr. Diamond noted, pigs would have been quite commonplace among peasant villages. When pigs were slaughtered for food the meat was often smoked in order to keep it from spoiling, so smoked ham and bacon was a staple of their diet. The term "bring home the bacon" was coined in the United States circa 1906 with regards to boxing, specifically. The first recorded instance is in telegrams relating the 1906 fight between Joe Gans and Oliver Nelson, in which Gans "brought home the bacon".

"Chew the fat" wasn't recorded in print until the 19th century. There are many debates about the meaning and origin of the phrase, but the one thing is clear is that it did not originate in the 1500s.

Those with money had plates made of pewter. Food with high acid content caused some of the lead to leach onto the food, causing lead poisoning death. This happened most often with tomatoes, so for the next 400 years or so, tomatoes were considered poisonous.

Not quite. Pewter could contribute to lead poisoning, but pewter was used for goblets, usually. Rich people had wooden plates, or sometimes stone plates. Poor people had plates made from bread called "trenchers". Regardless of the type of plate that they were eating on, they were not eating tomatoes as tomatoes are native to the Americas, not Europe. They could not have been in Europe until after Columbus returned from America with them. Europe was slow to adopt them mostly because they were unaccustomed to their taste and because they resembled other fruits that were known to be poisonous.

Bread was divided according to status. Workers got the burnt bottom of the loaf, the family got the middle, and guests got the top, or the upper crust.

One example from 1490 instructs people to "cut the upper crust of bread for your sovereign". However, most scholars agree that this was not a literal instruction, but rather an analogy to simply provide some of your food to your lord. The context in which it is presented here didn't come about until the 19th Century.

Lead cups were used to drink ale or whisky. The combination would Sometimes knock the imbibers out for a couple of days. Someone walking along the road would take them for dead and prepare them for burial.. They were laid out on the kitchen table for a couple of days and the family would gather around and eat and drink and wait and see if they would wake up. Hence the custom of holding a wake.

Wakes had little do with checking to see it people actually woke up, although that was one minor function. In most cases wakes served two purposes; pragmatically someone watched over the body to keep the vermin and small animals from feasting on it. Symbolically some religions, such as the Celts, believed that a spirit could only pass on to the afterlife in certain conditions; if there was a candle to light the way, if the window was open, etc. The Wake was intended to ensure that these conditions were met so that the soul could pass over. Although, more likely, these religious descriptions were adopted as an excuse for sitting there all night.

England is old and small and the local folks started running out of places to bury people. So they would dig up coffins and would take the bones to a bone-house, and reuse the grave. When reopening these coffins, 1 out of 25 coffins were found to have scratch marks on the inside and they realized they had been burying people alive... So they would tie a string on the wrist of the corpse, lead it through the coffin and up through the ground and tie it to a bell. Someone would have to sit out in the graveyard all night (the graveyard shift.) to listen for the bell; thus, someone could be, saved by the bell or was considered a dead ringer.

While there have been historical accounts of people being buried alive, it was certainly not as frequent as 1 in 25. And historically many graves were not dug up and reused. In ancient, pre-Christian England it was typical to burn the bodies of the dead rather than to bury them. This was common throughout most of the Celtic empire. There are many places in England with graves that still date back to before the 1500s. Although there were coffins with bells affixed to them out of fear of being buried alive, this happened during the 1800's at the peak of the cholera outbreak. These "safety coffins" featured bells described in the manner above, but they were not used in the 1500s.

"Saved by the bell" is actually an expression from boxing and refers to a fighter who is clearly about to lose, but the bell rings to end the round before his opponent can finish him off.

"Dead Ringer" comes from an 1888 newspaper article in the US in the Oshkosh Weekly. In the 1800's a "ringer" was a stand-in horse that was run in the place of another horse, or a horse that had its pedigree or name falsified. The "dead" part refers to a precise, absolute, or exact reckoning; Dead-ahead, dead right, dead on, etc. Thus, a "dead ringer" is a duplicate horse that looks like the original. Even the original article cites it in this context: “Dat ar is a markable semlance be shoo”, said Hart looking critically at the picture. “Dat’s a dead ringer fo me. I nebber done see such a semblence."

The graveyard shift is also not from the 1500s. It dates from the 19th Century as well. In 1895, the May 15th, New Albany Evening Tribune has a story about coal mining that features the expression; “It was dismal enough to be on the graveyard shift…” The most popular accounting of this expression is from the sea. According to Gershom Bradford in A Glossary of Sea Terms (1927), the watch from Midnight to 4am was called that “because of the number of disasters that occur at this time,” but another source attributes the term to the silence throughout the ship.

And that's the truth....Now, whoever said History was boring?

History is indeed interesting, but there's no reason to make up stories about it.

More and more I am beginning to realize that not everything that can be considered "truth" can be measured empirically. Often we write our own truths via our perceptions. Other times, we allow ourselves to be fooled by things that sound logical on the surface. A clever story can appear truthful on the surface, even if it is entirely inaccurate. I came across an example of this earlier this week that I will share here, during which time I will break it down and explain how this story, which appears to make logical sense, is largely inaccurate.

The story starts with a preface:

This is soooo interesting!! Totally feeling pretty blessed right now and not "piss poor"!

They used to use urine to tan animal skins, so families used to all pee in a pot & then once a day it was taken & Sold to the tannery.......if you had to do this to survive you were "Piss Poor"

But worse than that were the really poor folk who couldn't even afford to buy a pot......they "didn't have a pot to piss in" & were the lowest of the low. The next time you are washing your hands and complain because the water temperature isn't just how you like it, think about how things used to be.

In this first part the author of this tall tale begins with an element of truth; yes, tanners in the ancient world did use urine during the tanning process, particularly in Ancient Rome. This practice was well documented. However, this is not where the term "piss-poor" comes from. According to the Etymology Dictionary the term "piss" as an amplifier dates from WWII. And, in this particular case "poor" wasn't a reference to their financial status, but rather the quality of their work; ie: a Piss-poor mechanic. The first example of such is from 1940: Piss-rotten. The first recorded instance of Piss-poor comes from 1946. And while "didn’t have a pot to piss in" is an idiomatic expression which portrays destitution, it is also not from the 1500's. It first appeared in print in "Nightwood" by Djuna Barnes, which was published in 1936. The story goes on...

Here are some facts about the 1500s:

Most people got married in June because they took their yearly bath in May, and they still smelled pretty good by June.. However, since they were starting to smell . ...... . Brides carried a bouquet of flowers to hide the body odor. Hence the custom today of carrying a bouquet when getting Married.

Brides carrying flowers had nothing to do with their use as an air freshener. Flowers were symbols of fertility and feminism and it was believed that carrying flowers on their wedding day would bring a couple luck in conception. Also, bathing once per year was wrong. The lower class people did not bathe at all, for fear that the bath water would widen their pores and expose them to terrible diseases. The upper class people did tend to bathe, but they did so a handful of times each year, and certainly not on any set schedule.

Baths consisted of a big tub filled with hot water. The man of the house had the privilege of the nice clean water, then all the other sons and men, then the women and finally the children. Last of all the babies. By then the water was so dirty you could actually lose someone in it.. Hence the saying, "Don't throw the baby out with the Bath water!"

This is also incorrect. In many medieval cities there were public bath houses, which were common features since the Greco-Roman times. Aristocratic nobles who had a private bath often had a tub that was made from copper, bronze, or stone, so picking it up to dump it out would have been, for all intents and purposes, impossible. There was no modern plumbing during the 1500s, so filling up an entire tub with enough water to bathe an adult would have been a feat in and of itself, let alone the feat of engineering that would have been required to heat that amount of water. Poor people who did bathe and did not have access to a bath house typically just bathed in the local steam or pond. Now, to be fair, the phrase "don't throw the baby out with the bathwater" first appeared in 1512 in Germany. It was written by Thomas Murner in the book Narrenbeschwörung (Appeal to Fools). Scholars question the intent of this expression since the work in which it appears is satirical in nature. In the accompanying woodcut illustration the bucket that the woman is holding is clearly not large enough for an adult, which would lend support to the idea that the author was using this expression in an allegorical manner.

Houses had thatched roofs-thick straw-piled high, with no wood underneath. It was the only place for animals to get warm, so all the cats and other small animals (mice, bugs) lived in the roof. When it rained it became slippery and sometimes the animals would slip and fall off the roof... Hence the saying "It's raining cats and dogs."

Mice and bugs did, in fact, live in the straw thatched roof, that is certain. However, cats, and especially dogs, did not venture up there. The terms "raining cats and dogs" first appeared in the 17th century, not the 16th. There are number of theories about the meaning of this term, but the most widely accepted theory is that it is intended to evoke the image of a tumultuous engagement of a cat and dog fighting which the speaker is trying to equate the ferocity of the downpour to.

There was nothing to stop things from falling into the house. This posed a real problem in the bedroom where bugs and other droppings could mess up your nice clean bed. Hence, a bed with big posts and a sheet hung over the top afforded some protection. That's how canopy beds came into existence.

Canopy beds actually existed prior to the 1500s. The first iterations of these beds were used by nobles and aristocrats for two pragmatic purposes. The original canopy beds also featured curtains around all four sides that could be drawn closed. The first purpose that this served was to afford the sleeper some privacy from any other people who may also be sleeping in the room. But, more importantly, there was a mini-ice age going on during the middle ages and this curtain system provided extra warmth. Keeping the sheets clean would have been an added benefit and a by-product of the first two issues, but this is ignoring the fact that most nobles who could have afforded canopy beds would also likely have had solid roofs with wooden shingles.

The floor was dirt. Only the wealthy had something other than dirt. Hence the saying, "Dirt poor." The wealthy had slate floors that would get slippery in the winter when wet, so they spread thresh (straw) on floor to help keep their footing. As the winter wore on, they added more thresh until, when you opened the door, it would all start slipping outside. A piece of wood was placed in the entrance-way. Hence: a thresh hold.

"Dirt Poor" is not even a British expression, it's an American one, so there's no way that it dates from the 16th Century. Dirt Poor comes from the American Great Depression and is in reference to the Dust Bowl.

Also, people didn't add "thresh" to their floors. They kept Rush on the floor. Rush is a type of long, flowering grass. In modern times some places, particularly parish churches, will perform acts known as "rushbearing", where rushes are gathered up and strewn on the floor. While the lower classes would have probably used loose rushes, most higher status houses would have been furnished with woven mats made of rush. The term "thresh" means, "to trample". The threshold is the first place that you step inside of the home. Presumably you would trample the rush on the floor, but thresh is a verb, not a noun, so a threshold isn't used for keeping "thresh" inside.

In those old days, they cooked in the kitchen with a big kettle that always hung over the fire.. Every day they lit the fire and added things to the pot. They ate mostly vegetables and did not get much meat. They would eat the stew for dinner, leaving leftovers in the pot to get cold overnight and then start over the next day. Sometimes stew had food in it that had been there for quite a while. Hence the rhyme: Peas porridge hot, peas porridge cold, peas porridge in the pot nine days old.

Almost. Yes, most meals cooked in the pot were stew, and yes pease porridge could sit there for a couple of days, but often not more than 2 or 3 and only to improve the flavor. Peasants diets consisted of lots of breads and grains, including beer (beer was actually more sanitary than regular water). However, according to most accepted understanding of human development, such as that outlined by Professor Jared Diamond in Guns, Germs, and Steel, getting meat would not have been particularly difficult. Cows, Pigs, Chickens, and Sheep were among the first four animals domesticated for food. Even peasants would have had access to one of these on a pretty regular basis. Also, the leftover stew was often eaten for breakfast the next morning.

Sometimes they could obtain pork, which made them feel quite special. When visitors came over, they would hang up their bacon to show off. It was a sign of wealth that a man could, "bring home the bacon." They would cut off a little to share with guests and would all sit around and chew the fat.

As Dr. Diamond noted, pigs would have been quite commonplace among peasant villages. When pigs were slaughtered for food the meat was often smoked in order to keep it from spoiling, so smoked ham and bacon was a staple of their diet. The term "bring home the bacon" was coined in the United States circa 1906 with regards to boxing, specifically. The first recorded instance is in telegrams relating the 1906 fight between Joe Gans and Oliver Nelson, in which Gans "brought home the bacon".

"Chew the fat" wasn't recorded in print until the 19th century. There are many debates about the meaning and origin of the phrase, but the one thing is clear is that it did not originate in the 1500s.

Those with money had plates made of pewter. Food with high acid content caused some of the lead to leach onto the food, causing lead poisoning death. This happened most often with tomatoes, so for the next 400 years or so, tomatoes were considered poisonous.

Not quite. Pewter could contribute to lead poisoning, but pewter was used for goblets, usually. Rich people had wooden plates, or sometimes stone plates. Poor people had plates made from bread called "trenchers". Regardless of the type of plate that they were eating on, they were not eating tomatoes as tomatoes are native to the Americas, not Europe. They could not have been in Europe until after Columbus returned from America with them. Europe was slow to adopt them mostly because they were unaccustomed to their taste and because they resembled other fruits that were known to be poisonous.

Bread was divided according to status. Workers got the burnt bottom of the loaf, the family got the middle, and guests got the top, or the upper crust.

One example from 1490 instructs people to "cut the upper crust of bread for your sovereign". However, most scholars agree that this was not a literal instruction, but rather an analogy to simply provide some of your food to your lord. The context in which it is presented here didn't come about until the 19th Century.

Lead cups were used to drink ale or whisky. The combination would Sometimes knock the imbibers out for a couple of days. Someone walking along the road would take them for dead and prepare them for burial.. They were laid out on the kitchen table for a couple of days and the family would gather around and eat and drink and wait and see if they would wake up. Hence the custom of holding a wake.

Wakes had little do with checking to see it people actually woke up, although that was one minor function. In most cases wakes served two purposes; pragmatically someone watched over the body to keep the vermin and small animals from feasting on it. Symbolically some religions, such as the Celts, believed that a spirit could only pass on to the afterlife in certain conditions; if there was a candle to light the way, if the window was open, etc. The Wake was intended to ensure that these conditions were met so that the soul could pass over. Although, more likely, these religious descriptions were adopted as an excuse for sitting there all night.

England is old and small and the local folks started running out of places to bury people. So they would dig up coffins and would take the bones to a bone-house, and reuse the grave. When reopening these coffins, 1 out of 25 coffins were found to have scratch marks on the inside and they realized they had been burying people alive... So they would tie a string on the wrist of the corpse, lead it through the coffin and up through the ground and tie it to a bell. Someone would have to sit out in the graveyard all night (the graveyard shift.) to listen for the bell; thus, someone could be, saved by the bell or was considered a dead ringer.

While there have been historical accounts of people being buried alive, it was certainly not as frequent as 1 in 25. And historically many graves were not dug up and reused. In ancient, pre-Christian England it was typical to burn the bodies of the dead rather than to bury them. This was common throughout most of the Celtic empire. There are many places in England with graves that still date back to before the 1500s. Although there were coffins with bells affixed to them out of fear of being buried alive, this happened during the 1800's at the peak of the cholera outbreak. These "safety coffins" featured bells described in the manner above, but they were not used in the 1500s.

"Saved by the bell" is actually an expression from boxing and refers to a fighter who is clearly about to lose, but the bell rings to end the round before his opponent can finish him off.

"Dead Ringer" comes from an 1888 newspaper article in the US in the Oshkosh Weekly. In the 1800's a "ringer" was a stand-in horse that was run in the place of another horse, or a horse that had its pedigree or name falsified. The "dead" part refers to a precise, absolute, or exact reckoning; Dead-ahead, dead right, dead on, etc. Thus, a "dead ringer" is a duplicate horse that looks like the original. Even the original article cites it in this context: “Dat ar is a markable semlance be shoo”, said Hart looking critically at the picture. “Dat’s a dead ringer fo me. I nebber done see such a semblence."

The graveyard shift is also not from the 1500s. It dates from the 19th Century as well. In 1895, the May 15th, New Albany Evening Tribune has a story about coal mining that features the expression; “It was dismal enough to be on the graveyard shift…” The most popular accounting of this expression is from the sea. According to Gershom Bradford in A Glossary of Sea Terms (1927), the watch from Midnight to 4am was called that “because of the number of disasters that occur at this time,” but another source attributes the term to the silence throughout the ship.

And that's the truth....Now, whoever said History was boring?

History is indeed interesting, but there's no reason to make up stories about it.